Introduction

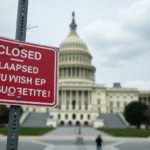

Throughout history, the United States has faced technological challenges from foreign competitors, from Sputnik in the 1950s to Japan’s electronics boom in the 1980s. Each time, the U.S. responded by strengthening its position—attracting global talent, investing in cutting-edge research, and enforcing antitrust laws—emerging stronger. However, today’s threat to U.S. technological leadership stems from internal erosion of fundamental advantages, with President Donald Trump’s policies appearing to dismantle the very pillars of American innovation.

The Four Pillars of U.S. Technological Leadership

1. Research Institutions

During the Cold War, bipartisan consensus supported ambitious programs like the Apollo mission and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Scientists and researchers enjoyed considerable intellectual autonomy. Key precursors to modern internet, such as J.C.R. Licklider’s “interactive computing” concept and ARPANET, originated within a deliberately loose federal-university network linking Stanford, MIT, UC Berkeley, Columbia, and other universities.

However, the Trump administration’s budget cuts have undermined this model: the National Science Foundation, NASA’s scientific direction, and the National Institutes of Health face reductions of 56%, nearly 50%, and around 40%, respectively. Such deep cuts, along with political fire tests for research grants, will stifle the ecosystem crucial for groundbreaking discoveries.

2. Talent

For over two centuries, the U.S.’s greatest advantage has been its ability to attract global talent. In the 19th century, Samuel Slater brought essential British industrial knowledge to U.S. factories. More recently, Hungarian biochemist Katalin Karikó spent decades in U.S. labs laying the groundwork for mRNA vaccines saving lives.

Yet, Trump’s drastic visa measures, international student bans, and hostility towards universities have made the U.S. less attractive to global talent. European research institutions now celebrate attracting top U.S. scientists, and the historic “brain gain” of the U.S. is perilously close to becoming a brain drain.

3. Competition

Unlike Japan, where a lax competition policy favored established conglomerates and stifled innovation, the U.S.’s robust antitrust regime historically focused on monopolies, fostering an entrepreneurial spirit. For example, the 1984 breakup of AT&T prevented a single company from monopolizing nascent internet, creating a competitive environment where innovation could flourish organically.

However, the U.S.’s commitment to vigorous competition has been weakening for decades. Industrial concentration is rising, fewer new companies are being created, and productivity growth is slow. Moreover, Trump’s tariff wall will accelerate this decline by protecting entrenched companies from foreign competitors and turning trade policy into a favor-for-hire system.

4. Impartial State

The U.S. learned during its Golden Age that unchecked monopolies and political corruption threaten growth. Congress responded with pro-competition reforms: the Pendleton Act of 1883 replaced patronage with a merit-based public service, and the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 curbed anti-competitive practices.

Today, these institutional safeguards are weakening. Trump’s proposed “F” list change would purge thousands of career government experts and replace them with loyalists, mirroring China’s President Xi Jinping’s approach where loyalty often outweighs competition. Similarly, the Office of Management and Budget—once led by Elon Musk—risks producing a less capable, more politically engaged bureaucracy. Agencies like the Internal Revenue Service have large staffs due to the U.S.’s overly complex and loophole-ridden tax code, which cannot be significantly reduced without regulatory simplification.

Conclusion

While the U.S.’s main competitor, China, also faces significant internal challenges, liberal democracies do not guarantee continuous technological progress. Innovation depends on openness, impartial norms, and robust competition. These advantages are rapidly deteriorating under the Trump administration. Sustaining innovation—the source of U.S. prosperity—requires actively defending institutions, not protecting industries.

About the Author

Carl Benedikt Frey, Associate Professor of Artificial Intelligence and Labor at the Oxford Internet Institute and Director of the Future of Work Program at the Oxford Martin School, is the author of the forthcoming book “How Progress Ends: Technology, Innovation, and the Fate of Nations” (Princeton University Press, September 16, 2025).

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 1995 – 2025

www.project-syndicate.org