Introduction

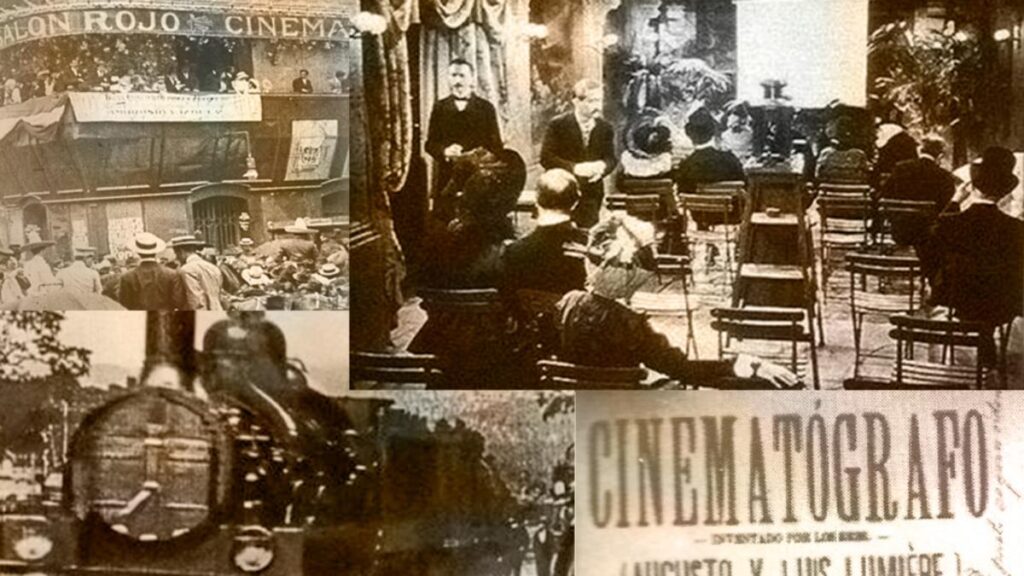

On August 6, 1896, the Chapultepec Castle opened its doors to host an invention brought by General Porfirio Díaz from France to liven up a small intimate dinner. The device, created by these so-called Lumière brothers, projected natural-sized images on a screen that sounded and moved as if they were real. This marked the beginning of cinematography in Mexico City.

The Intimate Gathering

The gathering was a success, despite initial shock and fainting. The Romero Rubio family and the general’s friends were captivated, learning that this contraption called “cinematograph” was a sensation in Europe, embodying progress. The joy and anticipation were so great that at the end of the show, guests repeated the soufflé of chicharrón, took more champagne and mezcal with worms, and the general allowed the fantastic machine to operate again, with exhibitions lasting until one in the morning. Before leaving, the president declared that Mexico had become the first country on the continent to enjoy such marvels of progress represented by the cinematograph.

Public Screenings Begin

Within fifteen days, the whole city learned of these wonders. Public screenings started on Friday, August 14. The exclusive concessionaires for Mexico, Messrs. Veyre and Bernard, representatives of the Lumière brothers and experts in operating the machine, set up in the basement of Plateros’ Droguery on the second street of the same name –later known as Madero– and placed large billboards announcing this new marvel. Ironically, this very spot would later become Mexico’s first movie theater: the famous Red Salon.

Overcoming Initial Fears

Despite some ladies and gentlemen’s fear of seeing “creatures as Christian as ourselves, yet animated by spirits like ours” on screen, the show went on. Around 1500 people attended, and due to high demand, programs were repeated every thirty minutes. The Monitor Republican reported the event, detailing the titles of the “views” offered, each lasting between 20 and 40 seconds: “The Waterer and the Boy,” “Card Players,” “Arrival of a Train,” “Herb Burners,” “Roller Coaster,” “Wall Demolition,” and “The Child’s Meal.”

Some viewings, especially the train arrival, caused panic as people feared the approaching locomotive would run them over. Ever since, we’ve had a fear of trains.

Rapid Public Adoption and Concerns

Within days, the public overcame their fear and began enjoying the confusion between fiction and reality. The desire to not miss anything sparked competition. Jacalin, coach houses, and vacant lots became “cinematographic salons,” and the dissemination became widespread. The novelty of “the view of the day” dominated conversations, becoming a topic some found degrading and dangerous:

- Question: What led to this decline in artistic production?

- Answer: Instead of picking up brushes, rulers, and paintbrushes, everyone flocked to sit in front of a screen when the cinematograph arrived. And they still haven’t returned.

Soon, “views” turned into short films with diverse themes. By 1900, the city had 22 establishments: salons for “decent people” and tents for “the plebs,” charging a real (approximately 5 cents) for the former and 50 centavos (approximately 2.5 cents) for the latter.

Porfirio Díaz and Early Cinema

With the advent of cinema, barely into the 20th century, General Díaz, delighted with the seventh art, commissioned over a dozen filming projects. Among them were scenes featuring him riding through Chapultepec’s forest and his wife, Carmelita Romero Rubio, riding in her carriage.

Cinema’s Enduring Allure

Over time, the “views” evolved into films, captivating audiences. Cinema, that painted mirror, genuine illusion, the devil’s invention, and an artist’s heart’s door opener, still enchants us. It arrived in the summer, during that distant month of August.