Understanding Matcha

Matcha, with its vibrant green hue and centuries-old tradition, is often regarded as a health-boosting superfood. But what sets it apart from regular green tea or a morning cup of coffee?

Like green and black teas, matcha comes from the Camellia sinensis plant. The difference lies in its cultivation and processing. While black tea is fermented, and green tea is simply dried, matcha is grown in the shade for several weeks before harvest.

This unique method alters the plant’s chemistry, enhancing compounds like chlorophyll and amino acids, giving matcha its distinct flavor and intense green color. The leaves are then dried and ground into a fine powder, hence its name, which means “tea powder” in Japanese.

Although associated with Japanese culture and Zen tea ceremonies, matcha originated in China. Brought to Japan in the 12th century by Buddhist monks for meditation, it became a fundamental element of Japanese tea culture, especially in formal ceremonies.

Health Benefits and Research

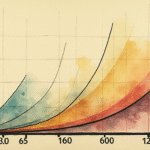

From a health perspective, matcha offers benefits similar to green tea due to its high polyphenol content, including antioxidants known as flavonoids. Since the entire leaves are consumed in powder form, matcha may provide a more concentrated dose of these beneficial compounds.

Matcha is known for its wide range of potential health benefits: antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, and even anticancer properties, along with potential cognitive benefits (stress relief, heart health, and blood sugar regulation).

However, most of the evidence supporting these claims comes from lab studies (on cells or animals), not solid clinical trials on humans. While initial research is promising, it’s far from conclusive.

One thing we know: matcha contains more caffeine than regular green tea but typically less than coffee. Caffeine, when consumed moderately, has well-documented health benefits, including improved focus, mood, and metabolism. There’s also evidence suggesting it may reduce the risk of certain diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

But in high doses, caffeine can cause side effects like insomnia, anxiety, and increased blood pressure. The “more is better” approach doesn’t apply here, and the optimal caffeine dose remains unclear.

Daily Intake Recommendations

Comparing matcha to coffee, both offer similar antioxidant properties and cardiovascular benefits. However, coffee has been studied more extensively, with clearer guidelines: three to four cups a day seems to be the safe upper limit for most people.

For matcha, recommendations are slightly more conservative, possibly due to its higher polyphenol levels. Some sources suggest one to three cups daily.

Tannins and polyphenols in both tea and coffee can interfere with iron absorption, especially from plant-based foods. Regularly consuming large amounts, particularly with meals, can increase the risk of iron-deficiency anemia.

Therefore, it’s advised to enjoy these beverages at least two hours away from meals, especially for those on a predominantly plant-based diet or prone to low iron levels.

Acidity and Digestion

Another consideration is that both coffee and matcha are slightly acidic and may cause digestive discomfort or heartburn in those with sensitive stomachs.

In conclusion, when deciding between coffee and matcha, remember that the latter contains L-theanine, an amino acid promoting relaxation. Thus, it may offer a gentler alternative for those prone to anxiety.