Introduction

As many countries grapple with an aging population, declining birth rates, labor shortages, and fiscal pressures, the successful integration of migrant populations has become an increasingly urgent issue. However, a recent study reveals that immigrants in Europe and North America earn nearly 18% less than native-born individuals. This analysis covers salary data from 13.5 million people across nine countries: Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the United States, between 2016 and 2019.

The Wage Gap Between Immigrants and Natives

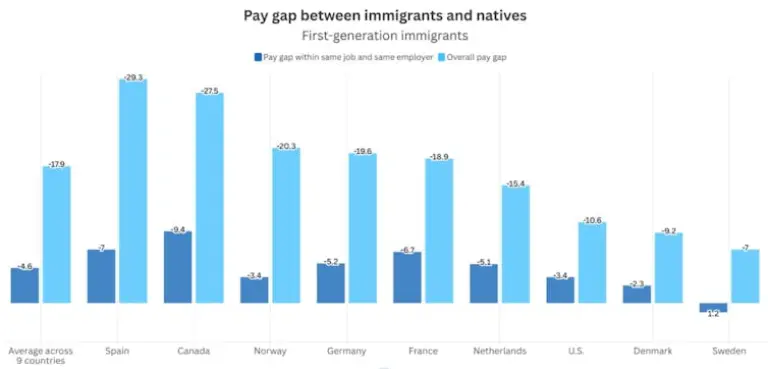

The wage gap primarily stems from immigrants’ limited access to well-paying jobs, with three-quarters of the gap attributed to restricted access to high-paying positions. Only one-quarter is due to salary differences between immigrants and native workers in the same job.

Link to image

Spain has the largest wage gap, while Sweden’s is the smallest.

High-income countries in Europe and North America face similar demographic challenges, with low fertility rates causing population aging and labor shortages. While pro-natalist measures are unlikely to alter this demographic fate, robust immigration policies can help address these issues.

In all these countries, despite vastly different labor institutions and migrant populations, a common theme emerges: they are not effectively leveraging the human capital of immigrants.

Regional Disparities

The study found that immigrants earn 17.9% less than natives on average, but the wage gap varies significantly between countries. In Spain, which has hosted a large number of immigrants in recent years, the gap exceeds 29%. In Sweden, where many immigrants find work in the public sector, it’s only 7%. These results exclude those who are unemployed or work in the informal economy.

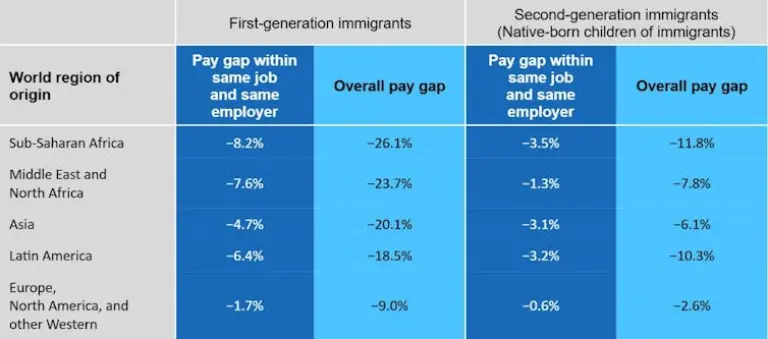

Origin also plays a role. The highest average salary disparities were observed between migrants from sub-Saharan Africa (26.1%) and the Middle East and North Africa (23.7%). For those from Europe, North America, and other Western countries, the salary difference relative to natives was much smaller, at 9% on average.

Link to image

Wage disparities among immigrants by region of origin.

The study also suggests that the children of immigrants have significantly better salary prospects than their parents. In countries with data on the second generation –Canada, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden–, the difference narrowed over time: their offspring earned on average 5.7% less than native workers with native-born parents.

Difficult Access to Better-Paying Jobs

Beyond quantifying the gap, we aimed to understand the roots of salary disparities. To create better policies, it’s crucial to know if immigrants earn less than natives for the same work in the same company or if these differences result from immigrants typically working in lower-paying jobs.

By a wide margin, we found that immigrants end up working in sectors, occupations, and companies with lower wages; three-quarters of the difference is due to this labor market selection. The salary difference for the same work in the same company was only 4.6% on average across the nine countries.

These disparities reflect a failure of immigration policy to integrate migrants, as they are confined to jobs where they cannot fully utilize their potential. Our analysis disproves the notion that the lack of access to better-paying jobs is merely a reflection of the qualification difference between immigrants and native workers. We also found that the magnitude of the salary gap and the crucial role of unequal access to well-paying jobs is similar for both university-educated and non-university-educated immigrants.

This implies that the salary difference between immigrants and natives largely represents market inefficiency and failed policies, with significant social consequences for both migrant populations and the countries that host them.

Policy Implications

While policies ensuring equal pay for the same work may seem like a viable solution, they won’t close the wage gap for immigrants. This is because they only help those who have already secured employment, while migrants face labor market barriers long before even applying for a job. These barriers include complex validation processes for university degrees or other qualifications and exclusion from professional networks.

Therefore, policies should focus on facilitating access to better jobs.

To achieve this, governments must invest in programs such as language training, education, and vocational training for immigrants. They should ensure early access to employment information, professional networks, job-seeking assistance, and employer references. They should implement standardized and transparent recognition of foreign titles and credentials, helping immigrants access jobs that match their skills and training.

This is particularly important for Europe, which is rapidly trying to attract and retain skilled immigrants who might be reconsidering their decision to move to the US in the era of Trump. In the European Union, around 40% of non-EU immigrants with university degrees hold jobs that don’t require a degree, known as brain waste.

Some countries are already taking steps to address this issue. Germany’s Qualified Immigration Act, effective in 2024, allows foreign title holders to work while their credentials are officially recognized. In 2025, France reformed its Passeport Talent permit to attract skilled professionals and tackle labor shortages, especially in the healthcare sector.

These policies help ensure that foreign workers can contribute their full potential, and that countries can maximize the benefits of immigration in terms of increased productivity, higher tax revenues, and reduced inequalities.

If migrants cannot access good jobs, their skills go underutilized, and society loses out. A smart immigration policy doesn’t end at the border but begins there.