The Traditional Perspective on Muscle Knots

For decades, muscle knots have been one of the most common diagnoses in physiotherapy, sports medicine, and primary care consultations. Many people have experienced that uncomfortable sensation of a “knot” or “tight muscle” in their back or neck. Traditionally, these discomforts have been attributed to overexertion, poor posture, stress, or muscle weakness.

Challenging the Traditional Model

However, recent research suggests that the situation might be more complex than previously thought. Instead of simple muscle contractions, muscle pain could involve the nervous system, pain perception, and the patient’s emotional context.

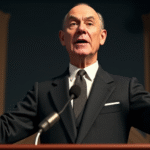

Arturo Goicoechea, a Spanish neurologist and science communicator specializing in neuroscience of pain, is one of the key figures questioning the traditional model. He states: “Muscle knots do not exist as structural or mechanical entities in the traditional sense, but rather as expressions of central nervous system protection programs that can be modified through understanding and addressing pain appropriately.”

This assertion is supported by advancements in neuroscience, which have demonstrated that the central nervous system can generate pain and stiffness as a protective response, without actual tissue damage.

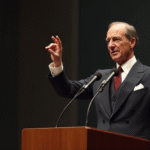

Lorimer Moseley, a prominent Australian researcher in chronic pain, agrees with Goicoechea: “Many pains we attribute to muscle knots are actually due to nervous system sensitization. The brain interprets a threat and generates a sensation of stiffness, even though the muscle is perfectly healthy.”

The Disconnect Between Perception and Reality

This discrepancy between perception and reality points directly to a centralized pain processing mechanism, where the brain interprets, amplifies, or distorts somatic signals based on emotional, cognitive, and contextual factors.

This idea has significant implications. If what we perceive as a muscle knot is actually a brain perception, treatments focusing solely on “warming up and massaging knots” might not be sufficient.

A Challenged Paradigm

The therapeutic approach through physiotherapy stems from the traditional interpretation that considers muscle knots as simple, maintained muscle contractions. However, this idea has been progressively questioned in recent years by neuroscience and physiology.

Some of these criticisms challenge the traditional paradigm, leading to studies on muscle tissue imaging and functional analysis. These reveal that in many cases, there are no structural or mechanical alterations to justify the pain and stiffness reported by patients.

These findings are possible thanks to ultrasound cutaneous elastography, an advanced technique that allows real-time evaluation of muscle tissue elasticity.

Some studies have detected minimal variations in the viscoelasticity of areas perceived as “knotted,” but there’s no clear correlation between these data and the reported pain intensity by patients.

Another study using these advanced techniques found no significant differences between painful and healthy muscles, reinforcing the idea that there isn’t always an observable physical alteration.

Moreover, if a sustained muscle contraction existed, there should be increased electrical activity in the affected muscles, measurable through electromyography (EMG). However, some systematic reviews show that this hypothesis lacks consistency since there isn’t always evidence of abnormal activity in painful muscle points.

Instead, similar neuromuscular patterns are detected between subjects with and without symptoms, suggesting a more perceptual than physiological component.

Evidence Points in Another Direction

Another aspect related to muscle knots is what’s known as “trigger points.” Their analysis also proves to be quite revealing, as widely accepted in clinical practice, their existence as a specific anatomical entity has been questioned.

Authors of a 2015 review published in Rheumatology state that there’s no conclusive evidence of trigger points being identifiable pathological structures, proposing instead a model based on nervous system sensitization.

These evidences don’t completely invalidate the idea that muscle alterations might exist in certain clinical cases (like fibrosis or pathological contractures after severe neurological injuries), but they do demand a critical review of how muscle pain is diagnosed and treated in most patients.

In essence, current science compels us to abandon simplistic explanations: the pain and stiffness perceived as muscle knots don’t always correspond to visible muscle anomalies.

It’s a complex phenomenon where the nervous system, pain memory, and the patient’s emotional environment play a crucial role.

Rethinking Pain Education

All signs suggest that revising how muscle knots are diagnosed would be beneficial. However, should we also reconsider the treatment approach? Should therapeutic methods change, or should we continue with treatments that may not validate the diagnosis?

Currently, there’s a push to focus on the nervous system, setting aside massages, heat, or stretches. This means reducing hypervigilance, encouraging active movement without fear, and providing pain education. Understanding it is often the first step to alleviating it.

One of the main reasons driving this new treatment line is the language we use. The way we name and explain pain influences how patients experience it.

Talking about “muscle knots” can reinforce the idea that the muscle is damaged or “trapped,” promoting fear of movement and fostering passivity, as patients expect someone to “undo their knot.” This can lead to chronic pain.

Therefore, many experts propose replacing this term with more fitting ones like “muscle pain,” “rigidity sensation,” or “body’s adaptive response.”

Pain is Real, and So Are Its Solutions

Although muscle knots as we understand them may not exist mechanically, the pain patients feel is real. This demands effective, empathetic, and evidence-based responses.

Neuroscience encourages us to look beyond the muscle, question deeply held beliefs, and evolve towards a more informed and humane approach to pain management. If pain is an alarm signal, perhaps the best treatment isn’t disabling the muscle but calming the guardian watching over it.