Venezuela’s hydrocarbon sector has long been a battleground between the state and private companies, subject to recurring cycles of liberalization followed by petro-nationalizations. These nationalizations tend to resurface when oil prices are high, new abundant reserves are discovered, or extraction volumes increase, as was the case in the 1970s and early 2000s.

The First Cycle of Petro-Nationalism: The Origin of PDVSA

Between the 1920s and 1950s, extraction was controlled by foreign companies like Shell (UK-Netherlands) or Standard Oil and Gulf Oil (EU). In the 1950s and 1960s, the Venezuelan state increased taxes and royalties and renegotiated concessions to gain more sovereignty over its raw materials.

Reventón del pozo Barroso II en Cabima, estado Zulia, el 14 de diciembre de 1922. Fuente: Wikipedia.

As a result, private investment and crude production gradually declined in the 1960s-70s, and Carlos Andrés Pérez’s administration carried out the first petro-nationalization on January 1, 1976. However, it was not an abrupt nationalization; negotiations were made with multinationals who were compensated. Despite being 100% state-owned, PDVSA could operate with autonomy and minimal political interference.

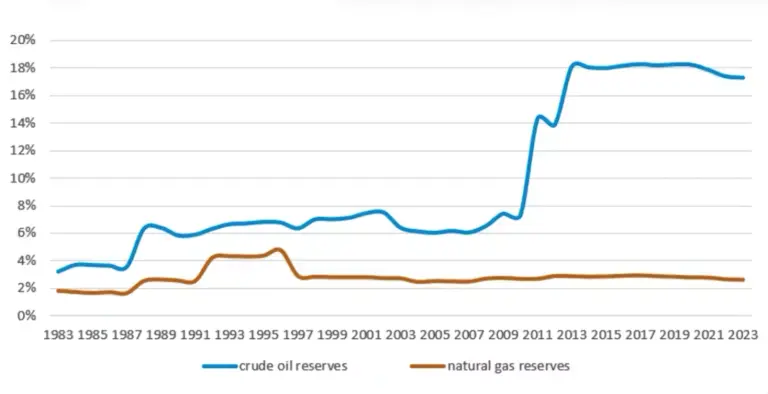

Reservas de petróleo y gas natural venezolanas en % de las reservas mundiales. Fuente: US Energy Information Administration.

The second cycle of liberalization and large investments began in the 1990s due to the state’s inability to cover exploration and exploitation expenses of Venezuela’s heavy oil from the Orinoco Belt. Multinational companies were offered a special contractual framework with broad guarantees against political changes.

The Second Cycle of Petro-Nationalism: The Chavismo

Hugo Chávez came to power in 1999 and was always critical of opening the oil sector to foreign capital. However, he avoided changing the contractual and fiscal regime until 2005. This delay was explained by the guarantees offered by the 1990s contracts and the fact that multinationals were still carrying out significant investment projects between 1999 and 2004.

The rise in oil prices between 2004 and 2013, the completion of projects with multinational companies, and the dismissals of oil workers who participated in the 2002-2003 general strike encouraged the chavista government to tighten fiscal conditions and renationalize the sector in 2007. More than a total expulsion of foreign companies or generalized confiscation, it was a political and contractual renationalization. This process served to capture and redistribute petroleum rents, turning PDVSA into a political instrument serving the regime.

Between 2003 and 2012, numerous social projects were carried out financed by petroleum rents, known as the Bolivarian Missions. They were very popular as they reduced poverty and inequality. However, they also exacerbated the rentier character of the state without improving the sector’s productivity or diversifying the economy. Instead, the result of renationalization was the collapse of long-term investment and oil extraction, limiting the incorporation of new technologies.

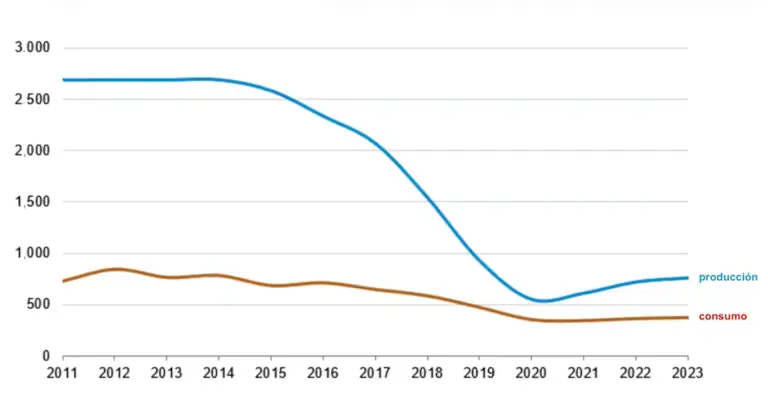

Production and consumption of petroleum products in thousands of barrels per day. Source: US Energy Information Administration.

When Nicolás Maduro took office in 2013, he inherited a system of missions entirely dependent on petroleum revenues that, starting in 2014, began a free fall due to the decline in PDVSA’s production, the drop in international prices, and domestic hyperinflation.

Maduro dismantled several redistributive missions and kept only those for mere subsistence to avoid social outbursts and reinforce political clientelism.

The government attempted to attract foreign investment, including operators from allied countries like Russia or China, to extract oil from the Orinoco Belt and gas in deepwater. However, social instability, economic collapse, and US sanctions had discouraged multinationals.

What is Trump’s Interest?

The 2014 petro-nationalization was not illegal, as the natural resources belong to Venezuela, nor a generalized confiscation. However, two US oil companies –ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips– refused to collaborate with the Chavista government, while Chevron continued operating. The state expropriated the assets of non-compliant multinationals, and both companies faced years of international litigation, which they won. However, the Venezuelan state has yet to fully pay the compensations due to the economic collapse.

It is true that, despite having the largest global crude reserves, Venezuela’s petroleum sector suffers from chronic underinvestment and a lack of skilled personnel. Moreover, these reserves are heavy oil, highly viscous and with a high carbon footprint. This results in elevated refining costs, though it is suitable for US Gulf Coast refineries.

According to Rystad Energy, Venezuela would need to invest $110 billion to restore production levels from 15 years ago—double what US oil companies invested globally in 2024. It remains to be seen if these companies will show the same enthusiasm as Trump for Venezuelan oil, especially given the current scenario filled with politico-legal uncertainties and relatively low prices.

Therefore, it seems more relevant that the US interest lies in preventing its political rivals—Russia, China, and Iran—from controlling Venezuelan oil and turning it into a strategic weapon in the future.